When Neil Young announced he was pulling his entire discography from music streaming giant Spotify over the platform’s alliance with podcaster and vaccine skeptic Joe Rogan, the beloved singer-songwriter explained in a open letter that he was taking a moral stand.

“I am doing this because Spotify is spreading misinformation about vaccines – potentially causing the death of those who believe the misinformation is being spread by them,” Young wrote, concluding, “They may have Rogan or Young. Not both.” Soon after, Spotify granted his request and removed Young’s entire discography.

In issuing the statement, Young, 76, was launching the latest campaign in a decades-long artistic battle against corporate media and power structures that prioritize profit over art.

“Artists are manipulated by business all the time,” Young told a British radio interviewer in 1992, of his approach to running his business. “A lot of artists are weak when it comes to their own direction and their own future. A lot of them just put themselves in other people’s hands and then feel frustrated that things aren’t going well.

Over the decades, Young has made headlines for indicting: MTV commercial ties; musical peers including Eric Clapton, Michael Jackson and the Rolling Stones for earning millions selling their music for commercials; the market-driven tastes of record mogul David Geffen; Monsanto and corporate control of family farms; the owner of Lionel trains for announcing its closure (Young ended up buying the company); the sonic inferiority of compact discs; and how tech companies have been willing to compromise on audio quality for bigger profit margins.

“Neil has this passionate belief in things, and when he believes in something, he follows through,” says longtime record producer and publicist Bill Bentley, who worked with Young at Reprise Records and currently writes a column for the artist’s Neil Young Archives online hub. “I don’t think I’ve ever met another artist so determined to stand up for what he thinks is right. Neil doesn’t change his perspective on what it’s going to cost him in sales or whatever.

His discography confirms it. Beginning as a folk singer in the 1960s, Young’s repertoire includes righteously outraged songs about institutional violence (“Ohio”), racial inequality in the South (“Southern Man”), religious extremism and violence ( “Let’s Roll”) and political expediency. (“Let’s impeach the president”). He even released a concept album about the dangers of biotechnology called “The Monsanto Years”.

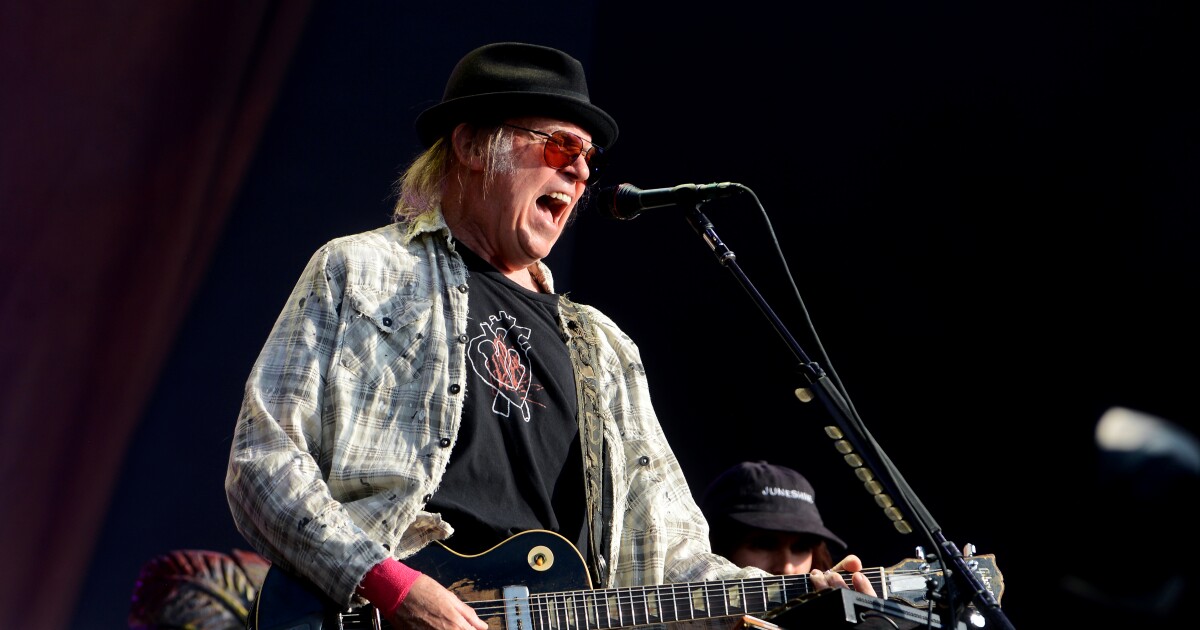

Neil Young in 2014.

(John Shearer/Invision/AP)

Young’s issue with Spotify, which is the world’s top music broadcaster with more than 172 million paying subscribers, mirrors a similar skirmish he initiated in 1987 with cable network MTV. At the time, the video giant was the dominant force in popular music; being added to the channel’s rotation was a key to ensuring a song’s commercial success.

In response and to protest against this power, Young wrote a song called “This note is for you.Inspired by an idea from a “This Bud’s for you” ad campaign airing at the time, Young began the lyrics while on a tour bus: “I don’t sing for Pepsi / I don’t sing for Coke”.

“The Rolling Stones were sponsored by Jovan perfume, Eric Clapton and Steve Winwood sold beer, Michael Jackson was bought by Pepsi for $15 million,” Young told interviewer Mark Rowland, quoted in the authorized biography. by writer Jimmy McDonough in 2002, “Shakey: Biography of Neil Young.”

“He complained about the hyper-commercialization of pop music and the fact that marketers stuck their logos on tours, even if there was no specific relationship,” recalls Bob Merlis, former vice president Senior Corporate Communications for Warner Bros. Records. Merlis oversaw the “This note is for you” press campaign.

Young’s intention was to expose the disproportionate power that MTV had accumulated with both consumers and advertisers. His team hired Julien Temple to direct the video for the song, which ridiculed Jackson, Whitney Houston and Budweiser mascot Spuds MacKenzie. MTV rejected the clip. Outraged, Young wrote an open letter.

The ensuing press attention earned Young an invitation to appear in a segment with MTV News’ Kurt Loder. Explaining why he would appear on a network he so strongly criticized, Young said, “You guys are so fat that if I don’t come here, not only can I air this video, I can’t air the next one. video. . How am I supposed to know?” MTV, Young concluded, “should be called music television, not music television.”

Eventually, MTV relented and aired the video, which ironically won Video of the Year at MTV’s 1989 Video Music Awards. “I still can’t believe such a silly little song helped resurrect my career the way it did,” Young told writer Nick Kent.

Says Merlis, “He’s the definition – and I don’t mean that in a negative way – of fair. He is consistent in avoiding any possibility of him being perceived as a sellout. It’s embedded in his DNA. He is incapable of being corrupted, and he is his own man. Adds Merlis with a laugh: “His bandmates would tell you that too – for better or, sometimes, for worse.”

Less than a decade earlier, Young had faced an equally formidable cultural force: record mogul David Geffen. After being wooed away from his longtime home of Warner Bros. subsidiary Reprise Records following the release of his album “Re-ac-tor” in 1981, Young began work on his debut album Geffen. At the time, Young was experimenting with electronic music – going so far as to collaborate with synth punk band Devo for the 1982 film “Human Highway”.

Understandably, musical experience bled into Young’s next recording project, which, per the Geffen contract, gave him a hefty budget.

Called “Trans,” the synth-focused new wave album featured Young filtering his vocals on many songs through a Vocoder vocal distortion box and relying on synthesizers as much as his usual guitar. It flopped upon release in 1982. His next album, with an equally impressive budget, was a rockabilly-inspired album simply recorded with his band the Shocking Pinks called “Everybody’s Rockin'”. Although the video for the single “Wonderin'” was shown on MTV, its impact certainly did not match its work in the 1970s.

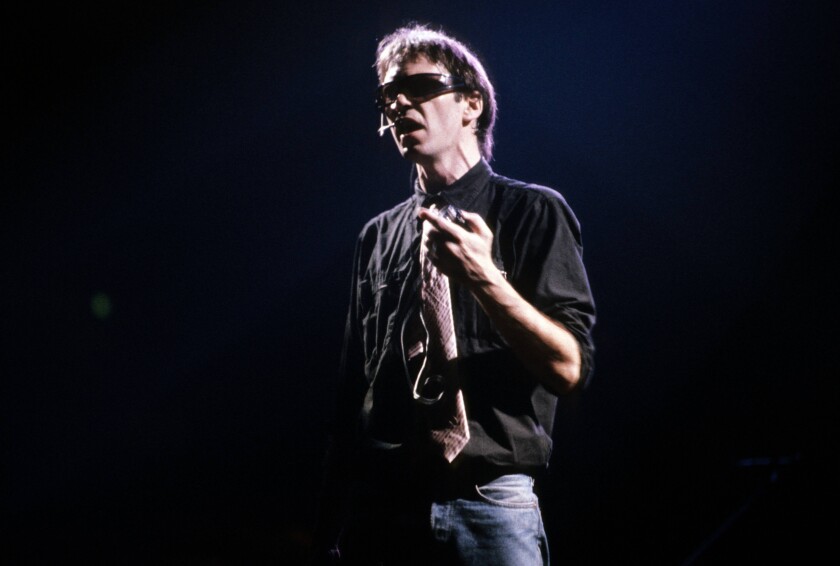

Neil Young performs music from his 1982 album “Trans”.

(David Redfern/Getty Images)

Angry that Young was not providing “Neil Young” style music, in 1983 Geffen sued Young for over $3.3 million. previous recordings.

“David took it personally that I was making records on his label that weren’t selling,” Young told McDonough. Later, Young brushed off criticism that his recordings of Geffen were self-indulgent, telling interviewer Tom Hibbert, “I did ‘Trans’ because I wanted to…and if you don’t like it, It’s okay.”

In response, Young counterattacked. Ultimately, the injured parties dropped the lawsuits and settled out of court. “I could understand where Geffen was coming from,” Young told McDonough. “He had a tough argument to hoe. He wanted to win a million dollars – and I was in another world.

Young rarely tempered his beliefs, whether they offended liberals or conservatives. The news page of his Neil Young Archives site, after all, is called the NYA Times-Contrarian.

His own track record is not without blemish. In 1985, as AIDS swept through America’s gay communities, Young used a homophobic slur in an interview and said of gay people and the virus: “You go into a supermarket and you see behind the f— cash register, you don’t want him looking after your potatoes.

During the 1990s, Young lamented the rise of compact discs and the loss of the tactile nature of vinyl. As file sharing spawned iTunes and the iPod era, Young set his sights on big tech, telling The Times in 2009, “Apple has turned music into wallpaper.” He rejected the limitations of MP3 sound quality and decried how digital compression had ruined the music listening experience.

Its response was an admirable, if tilting, entry into the tech sector with a portable digital music player called Pono and an accompanying online download store. Billed as a portable player more faithful than the iPod – but yellow and triangular like a Toblerone chocolate bar – Pono was funded in part by another recent innovation, crowdfunding. Upon its release in 2015, Pono became the subject of late-night monologues and online chatter, but did little to shake up the tech landscape. Ars Technica’s review at the time called the Pono “a great refreshing snake oil drink”. The company ceased operations in 2017.

Bentley says that regardless of the outcome of Young’s most recent position, the singer’s tenacity remains stronger than ever.

“I don’t know where the Spotify war will end – those kinds of wars, in the end no one wins,” Bentley says. “But I know Neil doesn’t back down once he thinks he’s doing something that feels right to him.”