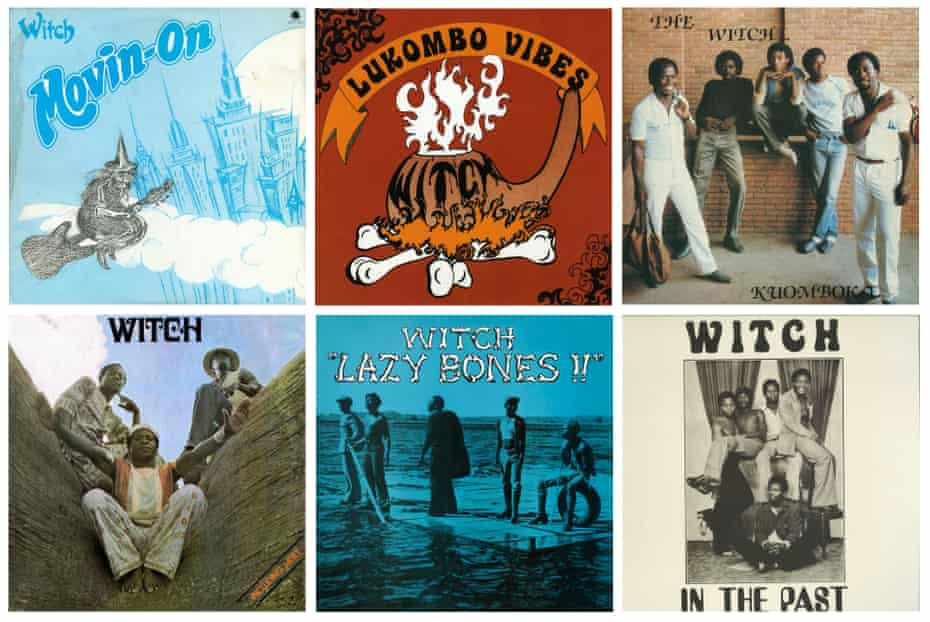

Emmanuel Chanda works as a gem miner in the Zambian countryside, blasting rock faces in search of amethyst. Surrounded by rock and noise, there is a poetic similarity to what he’s best known for: electrifying a nation as the frontman of Witch, Zambia’s most popular band of the 1970s who released five full albums. in as many years and has been the driving force for the Zamrock movement for the decade. Blending African beats and garage rock inspired by imports from the country’s former British settlers, they were nicknamed the Beatles of their country and were renowned for their incendiary seven-hour concerts conducted by Chanda, for whom the stage was just too small.

Almost 45 years after his last studio recordings with the band, Chanda – known as Jagari, after Mick Jagger – has regained some of his stardom. A new documentary by Gio Arlotta, Witch: We Intend to Cause Havoc, has just been released, and traces the band’s legacy from the mines of Zambia’s Copperbelt province to festival stages in Europe after an unlikely revival which, in the late 2010s brought Witch out of Africa for the first time.

The renewal, he said on the phone from the Zambian capital Lusaka, “gave me a new lease of life, a new lease of life to my talent and to the career that I have adored”. It means even more in the aftermath of a tragedy. “From the original configuration,” he explains, “I’m the only one still alive.

Chanda, now 70, was born in Kasama and raised by his older brother amid a “cross-pollination of cultural activities” in the mining town of Kitwe, the capital of the Copperbelt in what was then known as Northern Rhodesia. “We only had one way to listen to music,” he says, recalling his school days writing lyrics he heard on British radio shows and reading Melody Maker magazine, the only music publication available. “The Top 20 fascinated me,” he says. “The Rolling Stones, the Hollies and Jimi Hendrix… In fact, in my day, anyone who couldn’t play hi Joe was not considered a good guitarist.

He lets out a warm little laugh as he says this, the kind of laughter that could fill a room. The same laughter punctuates much of Arlotta’s documentary, where Jagari’s beaming smiles and resounding high fives hint at the captivating presence for which he was once famous as a frontman. His classmates also saw his star power and pushed him to join a band after seeing him thrive at social functions and ballroom dancing.

Bands such as Black Souls, Peace and Fire Balls were a scene in Kitwe that was reproduced across the Copperbelt. When Kenneth Kaunda came to power as the first president of the newly independent Zambia in 1964, he issued a decree that 95% of the music on Zambian radio must be of Zambian origin. It spawned a new wave of rock bands mixing original compositions with covers of Sympathy for the Devil and We’re an American Band from Grand Funk Railroad (or We Are a Zambian Band, as Witch played) . “We called it Zamrock,” Jagari explains. “Zambian rock that we all made.”

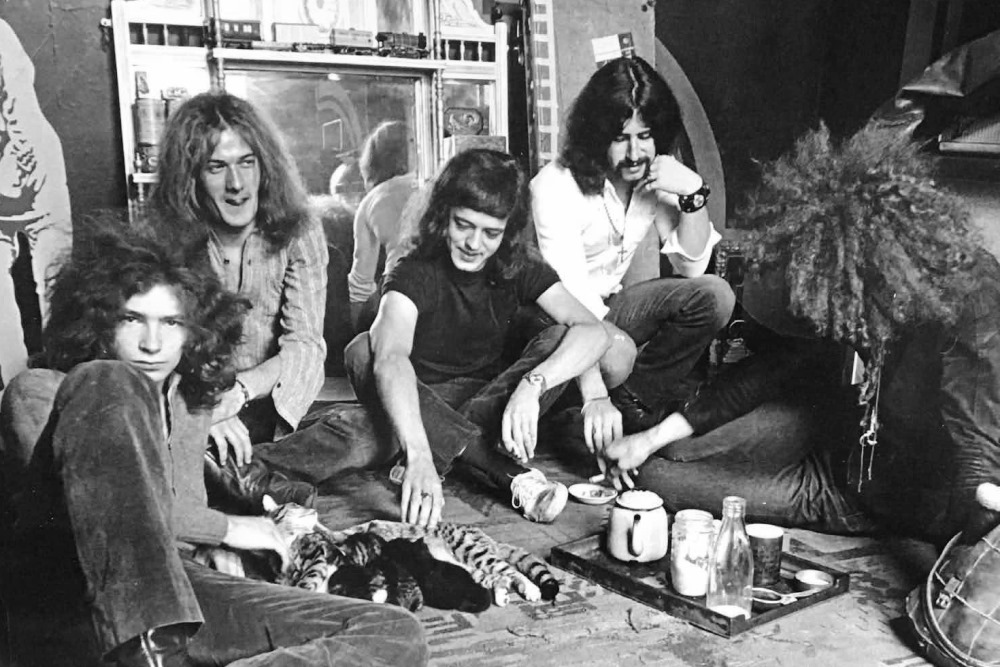

Most of the groups on Kitwe’s stage were Jagari’s own classmates. “We were all doing the same things,” he laughs. “Same music, same roadies, same girlfriends. But Witch, a fusion of Kingston Market, Boyfriends and Upshoots players formed in the early 1970s, has also strived to do something different. “We shouldn’t be imitators,” Jagari says of the band’s missive, merging “fuzz and wah-wah and keyboards” with “that mother tongue” of traditional African rhythms and percussion.

“The witch was the trailblazer,” says documentary maker Arlotta from her home in the Italian countryside. “When I heard for the first time [1975 track] Strange Dream, it kinda knocked me out, it was so distant and exotic. They sounded like psychedelic rock from the 60s and 70s, but the drummer is so much more groovy.

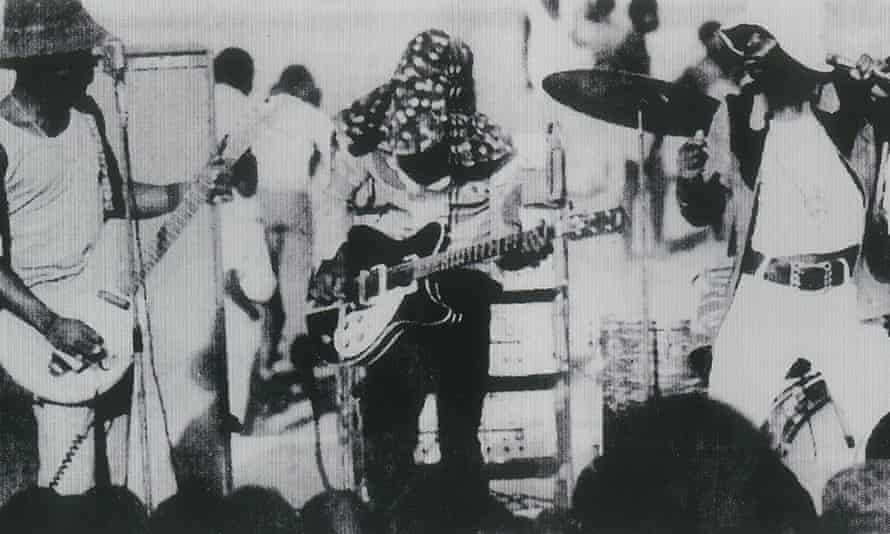

“We were adored by our audience,” says Jagari, recalling performances in Zambia, Malawi, Zimbabwe and Botswana. The fervor was so intense that police were called in to quell the riots apart from the oversubscribed shows: “The hall where the boys played had its roof ripped off as exuberant fans tried to force their way through the windows,” reads. one in a review of The Times of Zambia. .

Jagari took it in his stride. “Not to blow my own trumpet,” he said, “but people couldn’t compete. We drew big crowds because we were playing great music and the leader was full of antics. Oh, there were a lot of things that I did. There is another burst of that laughter. “Sometimes we would start at 7 am and [played] until 2 a.m. the next morning. Other times, I tossed a guitar into the crowd during the show, and before it landed, it was torn to pieces. Sometimes I wore women’s panties over my pants.

“Crazy,” Arlotta concludes, recalling a visit to one of the local venues where the band played. “There was one that had a theater with a stage and a balcony. Jagari used to jump from there when the band was playing – like in this scene from Quadrophenia.

By the time Jagari left the group at the end of the decade, Zamrock was in decline. Zambia plunged into an economic crisis in the mid-1970s as the price of copper – which accounted for 95% of the country’s export earnings – halved on the world market. Conflicts in Namibia, South Africa, Mozambique and Zimbabwe have encroached on Zambia’s borders. President Kaunda imposed curfews and blackouts from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m., rendering the Zamrockers powerless, and the arrival of disco in the late 1970s prompted Jagari to go out while his comrades group were pursuing a new direction. “Rock made me do something unusual,” he says. “But the disco didn’t move me that much.

Jagari is the only one left from the original incarnation of Witch. The AIDS epidemic, which would claim the deaths of up to 1.4 million people across Zambia by 2010, has reportedly claimed each of the men Jagari still calls “brothers”.

“Giddy King” Mulenga, “Star MacBoyd” Sinkala, Paul “Jones” Mumba, Chris “Kims” Mbewe and John “Music” Muma remain immortalized in Introduction – the intoxicating opening track from the band’s 1974 album from the same. name and de facto musical theme of Arlotta’s film – in which Jagari introduces his bandmates to the sounds of drum fills, guitar licks and frenzied organ solos. But later in life, the group – who once shared a house, training 9 am-5pm, Monday through Friday (“no girlfriends are allowed”) – split up.

“Paul Jones moved to Mansa and was looking for medicine, but he couldn’t find the person who was supposed to help him,” says Jagari, reciting a similar story for each of his former group mates. “When John Muma got sick, he called me. The day I arrived in Kitwe, he died. I stayed until the funeral. It made me sad that I couldn’t talk to him before he died.

Few could have anticipated Witch’s return afterwards, let alone Jagari, whose life was full of twists and turns. He had trained as a teacher after leaving the band, and by the early 90s was working as a high school lecturer and music director – until an unfortunate event briefly disrupted his career. Dropped by a group of questionable friends at an airport baggage claim, Jagari was taken into custody, tried, fined and then suspended from work after being falsely accused of importing drugs into the country. “It was everywhere on radio and television,” he exclaims. “The famous musician has been arrested!

Watching Arlotta’s documentary, you’d be forgiven for thinking that Jagari had been sentenced to years of forced labor. In an opening scene, the singer stands at the bottom of a rock cavity, surrounded by heavy tools. It almost sounds like that ominous scene in Martin Scorsese’s casino, where Joe Pesci’s reckless henchman is taken to the wilderness to be eliminated.

In fact, Jagari is a different rock star these days: he pursues his fortune in mines a six-hour drive north of Lusaka. “It’s not easy,” he said. “There are heavy rocks you have to blow up, and it takes me a long time to find what I’m looking for. It’s a lot of work, and I’ll be turning 70 soon. My energies are starting to run out. He intends to find a large pocket of gems and sell them, to fund the music school he dreams of retiring to, after spending nine years of his life serving as president of the Zambian company. copyright protection in music, as a mentor for Power in the Voice (a pan-African project encouraging young talent to realize their potential) and as a university professor.

All thoughts of retirement were thankfully put on hold, however, when Arlotta arrived at his door in 2014. The director reunited with the leader after making a detour on a transcontinental journey through Africa (Jagari arrived with a an hour and a half late for their first encounter with a guitar strapped to their back, Arlotta remembers). He had fallen in love with Witch’s music after hearing it for the first time through Now-Again Records, which reissued a collection covering the whole career in 2011. But even after two weeks spent with the frontman in his homeland, Arlotta felt that part of his film was missing, “to bring Jagari to Europe and document that. And it happened, and then that, things continued to snowball. “

With a new incarnation of the group (whose formation is captured in Arlotta’s film), Jagari returned to the stage in 2017 and reclaimed his status as Zambia’s greatest rock star, achieving what he and his brothers lacked. dreamed that in their heyday. “We have always looked forward to the opportunity to be exhibited in Europe and America,” says Jagari. “But he never came back then.”

Since 2021, Jagari has performed in Moscow, Paris, London and Amsterdam, at the international psychedelia festival in Liverpool (“I heard the loudest music of my life there. They said: it’s metal, my friend! ”) and the California Desert Daze Music Festival in Joshua Tree National Park. In December 2019, the Zambia National Arts Council awarded him a Lifetime Achievement Award, just two days before resuming a tour across the United States. “Sometimes when we put on a good show, they all come to mind,” Jagari says of his former band mates. “But I like these audiences in Europe and America. They give you hope. They give you the energy to keep going.

As for the future, Jagari hopes to be able to revive the group before retiring. “I’ve always composed,” he says, “and when I record something new, it won’t be too far from Witch.” Arlotta predicts Jagari will come back even better, saying that’s what he was made to do: “He’s a rock star.”